The Ministry of National Education of Turkey decided to make changes to the history curriculum, replacing the term «Central Asia» with «Turkestan». The news found a lively response in regional media, and many risked to suggest that in this way Ankara is again putting forward claims for hegemony in the Turkic world. However, in all likelihood, the decision of the Turkish authorities will not go beyond the toponymic discussion. Despite all attempts by Ankara to establish itself as a dominant force in the post-Soviet republics of «Turkestan», the time for this has long been missed. If it ever was at all.

Iran of stumbling

Interest in Central Asia, which is related to the Turks not only by common ethnic roots, but also by religion — Sunni Islam, — began to form on the shores of the Bosphorus in the 16th century, that is, in the era when the Turkish, or rather Ottoman capital had not yet moved from Istanbul deep into the Anatolian plateau, to the homeland of Angora goats and cats. As the caliph of all believers, the Ottoman sultan viewed the Turkic states formed in Central Asia on the ruins of the Golden Horde and the Timurid Empire as his potential if not subjects, then at least vassals.

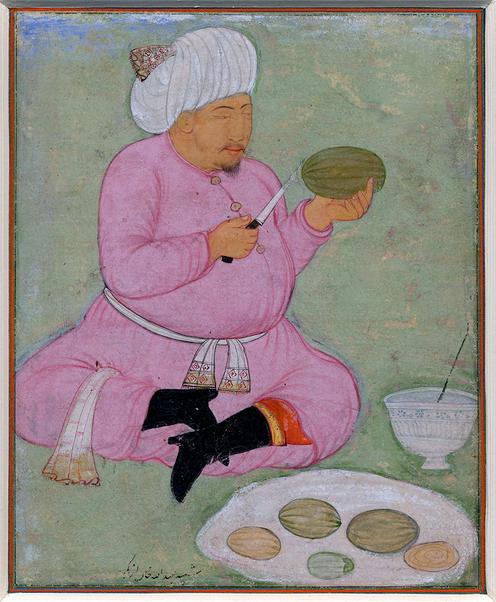

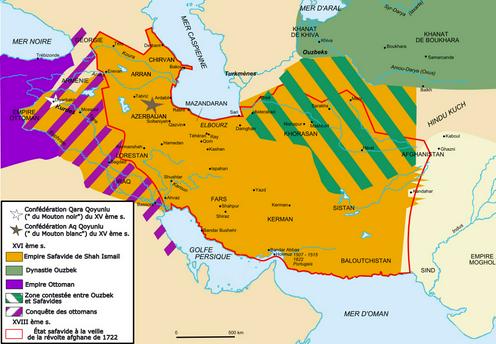

However, on the path of Ottoman expansion to the east stood several obstacles at once, each of which proved insurmountable. From the north it was the Muscovite, and later the Russian Tsardom, in the center — the Caspian Sea, and from the south Iran, where not friendly shahs from the Shiite Safavid dynasty ruled. Already the founder of the Shaybanid state, the first khan of the Bukhara Khanate Muhammad Shaybani established contacts with the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II to confront the Safavid Shah Ismail I. But that time it ended sadly for the allies, as Ismail's Kizilbash overcame the army of the Bukharans, and Muhammad himself lost his head.

Bayezid's son Selim I indirectly avenged the Persians by destroying the Safavid army in the Battle of Chaldiran, but the Ottomans could not take advantage of this victory — the limit of their conquests in the east for a long time was limited to the Armenian Highlands. Under Selim's heir, Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottomans reached the peak of their power, but this was done mainly through conquests in Europe, the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Had Suleiman transferred the main direction of his foreign policy activity to the east, who knows how the history of Central Asia would have turned out, but this discipline, as is known, does not tolerate the subjunctive mood.

At the same time, it is precisely in the era of Suleiman that, apparently, the first episodes of direct military cooperation between the rulers of Central Asia and Istanbul occur. In the middle of the 16th century, the sultan sent to Samarkand's Abdullatif Khan a detachment of 300 janissaries and gunners with artillery pieces, as well as masters in cannon casting. In this way, the Turks tried to stimulate the Samarkandians to joint action against Iran, but the Uzbek rulers arranged another internecine strife and the plan failed.

During the reign of Suleiman's son, Selim II, the Ottomans attempted to go beyond the Caspian from the northern side, where after the Russians consolidated in the Volga estuary, trade routes and Muslim pilgrimage routes (the aforementioned detachment of janissaries reached Samarkand by this route) connecting Central Asia with Crimea and Anatolia were threatened. However, the campaign against Astrakhan turned into a complete failure. As well as the attempt to dig a navigable canal between the Don and the Volga. Success in this case would have guaranteed the Turks a military presence on the Caspian Sea. Something they never managed to achieve.

Although, it seemed, at the end of the 16th century, when Murad III ascended the throne in Istanbul, all the chances for this were there. According to legend, at the beginning of his reign, the sultan asked his close associates which war of all those waged in the era of Suleiman I was the most difficult. Learning that it was the Iranian campaign, Murad conceived to surpass his grandfather and he succeeded, by 1580 the main forces of the Persians were defeated, and the Turkish army, occupying the territories of modern Georgia and Azerbaijan, established control over the western and southern shores of the Caspian.

The Shaybanid state at that moment was ruled by Abdullah Khan II, who also quite successfully fought against the Persians and, among other things, provided support to the Siberian Khan Kuchum in his confrontation with the Russians. Between Istanbul and Abdullah's capital Bukhara, permanent diplomatic contacts were established, in which the parties communicated almost as equals. Initially, the result of these contacts was a joint plan to attack Astrakhan. However, it was frustrated by the efforts of Russian diplomats and attacks on Ottoman possessions by Zaporozhian Cossacks, because of which the sultan had to use forces intended for the eastern campaign against them.

Focusing further on the joint struggle against Iran, Murad and Abdullah tore away a number of provinces from the Persian power and almost created a joint border. The Uzbeks, in particular, occupied Herat and advanced to Mashhad. It seemed that the moment of truth had come, but then the emperor of the Great Mughals, Babur's descendant Akbar, intervened in the Shiite-Sunni squabbles, deciding that although the Persians were heretics, the strengthening of Bukhara and the complete collapse of Iran directly threatened his power. News that Akbar was preparing an attack on Bukhara forced Abdullah to abandon the campaign to Mashhad, and this weakened the pressure on the shah.

Later, the ambassadors of the Uzbek khan were received rather coldly in Istanbul, despite Abdullah's promises to continue the war with the Shiites. Some historians believe that the reason for this was not Murad's disappointment in his ally, but on the contrary — his fears that, having crushed the Persians and reaching the border of the Ottoman Empire, the Uzbeks would become direct competitors of the Turks for hegemony in the entire Dar al-Islam.

Even when the Uzbeks led by Abdullah's son Abdulmumin Khan still took Mashhad, and their leader expressed readiness to «stand at the sultan's stirrup» and destroy Shiism at Murad's order, Istanbul took a pause. But Abdullah's appetites grew, he decided to attack Astrakhan on his own, and at the same time asked the sultan to allow him to proceed on the Hajj to Mecca through Istanbul, accompanied by an army of 10,000. Murad's reaction was to conclude peace with Shah Abbas of Iran behind the Uzbeks' back. Moreover, in 1592, seeing off the Persian envoy from Istanbul, he also promised that he would support the shah in his actions against the «Uzbek Tatars».

As a result, Abbas, having removed the threat from the west, moved his army against the Shaybanids and regained most of the lost lands. After the deaths of Murad and Abdullah, the Persians took full revenge, expanding their possessions along the entire perimeter of the borders.

Robe diplomacy

In subsequent years, the rulers of Central Asia, including the Kazakh khans, regularly sent embassies with gifts to Istanbul, offering the sultans either an alliance against the Russians, or joint actions against the Persians, or simply asking for help in the fight against internal enemies. The sultans wrote letters in response — most often to Bukhara, which they saw as the main political force in the region — but they could no longer provide real support to potential allies. The resources of the Ottomans, starting from the second half of the 17th century, did not allow them to pursue an active policy in the east. All the forces of the empire were thrown into confrontation with the Christian states of Europe, where the Turks entered a period of defeats that stretched for two and a half centuries.

The exception was perhaps only the military campaign of 1723-1727, when the Ottomans took control of even Tehran. But at that time they already had to act alone, since after the death of Abdullah II, the Central Asian states never reached the level of power that would allow them to participate on equal terms in the confrontation between the two main forces of the Islamic world.

When in 1735 the khan of Khwarezm Ilbars II began to complain to Sultan Mahmud I about the intrigues of the Iranian Nader Shah, who was preparing an invasion of Central Asia, Istanbul responded with formal replies and advice to resolve the matter with the Persians through negotiations. As a result, Nader Shah still conquered the Bukhara and Khiva khanates and turned them, albeit briefly, into his vassals.

But the Sublime Porte had no time for that — the second half of the 18th century turned for the Turks into a series of failed wars, primarily with Russia.

And then Istanbul remembered Central Asia again.

In 1776, the Ottomans tried to probe the possibility of creating an alliance with Bukhara, offering the local emir to incite the nomadic Kyrgyz and Kazakh tribes to raid the border areas of Russia. There was no reaction — Emir Daniyal-biy valued his relations with Catherine II too much.

Nine years later, the Turks again tried to persuade the Bukharans to attack the Russian borders and organize propaganda of the ideas of ghazavat (holy war — Fergana) among the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. Emir Shahmurad in return asked the Ottomans to help him in the fight against the Persians, as well as to send weapons and ammunition so that he could build fortifications on the border with Russia. This alliance also did not materialize — the Ottomans lost another war with the Russians, while the rulers of Bukhara were too busy with internal feuds. For the nomads, it was even more profitable to trade with Russia than to fight.

In the 19th century, the Iranian question faded into the background, Central Asia became one of the main directions of Russian expansion and, although contacts between Khiva, Bukhara, Kokand and Istanbul during this period were very active, they did not affect the real state of affairs in the region. At the same time, the parties regularly exchanged gifts: robes, horse harnesses, purebred horses, copies of the Quran and other religious literature. Various rulers of Central Asia continued to see in the face of the Ottoman sultan a mediator for settling regional disputes, their patron, and requested political support from him every time someone from subjects or neighbors encroached on their power.

In 1819, the Bukharan emir Haydar, who was pressed from all sides by enemies, even asked Istanbul for Ottoman suzerainty. Sultan Mahmud II convened a meeting of high officials and ulema to decide what answer to give to the emir. After long discussions, the statesmen decided that the annexation of Bukhara would bring the empire more harm than good, especially since the sultan is the caliph of all believers, de jure the emir is already his subject.

A large embassy to the sultan's court was sent in 1838 by the Kokand Muhammad Ali Khan, who asked the Ottomans to send military instructors and provide moral support in the struggle for primacy in the region with Khiva, Bukhara and the leaders of the Kazakh tribes. The khan did not receive military instructors, but instead received sound advice from Istanbul — to live in peace with his neighbors.

Painting depicting the Battle of Chaldiran between the Ottomans and Persians in 1514. Collection of the Chehel Sotoun Palace museum in Isfahan

Painting depicting the Battle of Chaldiran between the Ottomans and Persians in 1514. Collection of the Chehel Sotoun Palace museum in Isfahan

Hungarian traveler Arminius Vambery, who visited Khiva and Bukhara in the summer of 1863, wrote: «Among the population of Central Asia and its rulers, the Ottoman Empire enjoyed undoubted spiritual and political authority and occupied, in the opinion of ordinary people, almost the leading place in the system of international relations. And the sultan and emir, for example, appeared to ordinary residents of Bukhara as rulers of the world: poor people were delighted, speaking of the heroic deeds of their emir. They said that he penetrated from Kokand to China and, having conquered everything under his scepter in the east, also wants to conquer Iran, Afghanistan, India and Frangistan, all countries up to Rome itself; thus, the world was divided between the sultan and the emir."

When Russian troops began the war against the Kokand Khanate and occupied Tashkent, the Bukharan emir Muzaffar turned to the British and Turks for help. But the former refused immediately, as they themselves hoped to profit from the emir's possessions, and the sultan's government, after brief deliberation, once again advised Bukhara, Khiva and Kokand to join forces against the aggressor and independently resolve the issue of peaceful agreements with Russia.

«Our sincere concern as the head of Islam is to protect the welfare and ensure the security of Muslims in Central Asia. Nevertheless, I must regretfully admit that it is impossible to send material assistance due to the great distance, and also because there are other countries between us,» the sultan wrote to the emir.

The advice from Istanbul was ignored. After Russia subjugated the entire region, liquidating the Kokand and turning the Khiva Khanate and the Bukhara Emirate into its protectorates, the Ottoman authorities responded with refusals to the latter's request to help it in military reforms and send permanent diplomatic representatives. In Istanbul, it was considered that direct attempts to interfere in the affairs of Central Asia would bring nothing to the empire except the prospect of armed confrontation with Russia. And the latter, in turn, having learned about the negotiations, even forbade Bukhara and Khiva to conclude agreements with other powers without the consent of the Turkestan governor-general.

After this, the official relations of the Ottomans with Central Asia practically came to naught, although at the level of private individuals, educational and commercial organizations, they, on the contrary, began to develop rapidly. This made itself felt immediately after the February Revolution in Russia. However, then the British already stood in the way of the Turks to Central Asia.

In the footsteps of Enver Pasha

In 1908, as a result of an armed uprising, the Young Turks came to power in Turkey — a group of nationalistically minded intellectuals and young officers who received education in European countries and aimed at carrying out liberal reforms in the country. Under the influence of the Young Turks, various forms of Jadidism began to establish themselves in Central Asia, which originally arose among Russian Muslims as an ideology of Islamic modernism, but later acquired the form of a political movement.

The orientation towards reforms on the Ottoman model conditioned the pan-Turkic bias in Jadidism.

And the Young Turks themselves, after losing their last territories in Europe and Africa (as a result of the war with Italy and the Balkan Wars), began to literally echo the ideas of the Kazan Tatar Yusuf Akchurin, who argued that the supra-ethnic union previously supported by the Ottomans was unrealistic, and the empire would have a chance for the future only if it abandoned the Balkans in favor of Central Asia populated by related peoples.

In 1913, as a result of another coup d'état, the leadership of the empire passed to the «three pashas»: Enver Pasha, Talaat Pasha and Cemal Pasha. Having divided the main leadership positions in the country among themselves and plunging the empire into the First World War, the triumvirate made pan-Turkism virtually the basis of state policy. This was followed by various ethnic cleansings — Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians.

The Turks received the greatest chances to establish themselves, if not in Central Asia, then at least in the Caspian region, in a short period in 1918, between Soviet Russia's withdrawal from the First World War and the Mudros Armistice, which marked the final defeat of the Ottoman Empire. After the collapse of the Russian Caucasian front, Turkey, instead of withdrawing from the war on favorable terms itself, continued hostilities and not only regained the territories of Eastern Anatolia lost in previous years, but also occupied all of modern Armenia, Azerbaijan and part of Georgia. Thus, the Ottomans found themselves on the shores of the Caspian for the first time since the 16th century. Actually, from this time begins the special relationship between Turkey and Azerbaijan, which historically was more under the influence of Iran and which the Ottoman army supported in confrontation with the Armenians. Probably, if the Turks had more time and the British did not dominate the Caspian, the «three pashas» would have managed to penetrate into Central Asia in a similar way, but their army instead went to Dagestan, and then World War I ended.

Meanwhile, in Central Asia itself, pan-Turkic sentiments spread not only among some of the Jadids and autonomists (Kokand Autonomy). Subsequently, these ideas were also adopted by some of the leaders of the anti-Soviet rebels — the Basmachi. One of them, by the way, was that same Enver Pasha, who after being removed from power in his homeland cooperated with the Bolsheviks for some time, and then set out on his own.

Settling with his detachment in the mountainous regions of Eastern Bukhara, Enver Pasha conceived nothing less than to create a Turkic-populated empire of Turan on the territory of Turkestan, Afghanistan, Muslim lands of China and Siberia.

Other Basmachi leaders, for example, the authoritative Ibrahimbek, refused to support the pasha's Napoleonic plans. He did not find understanding in his homeland either, where Mustafa Kemal, who came to power, formed the Turkish Republic on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire and completely abandoned pan-Turkic doctrines.

In 1922, Enver Pasha was cut down by the Bolsheviks, and with him ended a whole era — until the very collapse of the USSR, any pan-Turkic ideas in Central Asia were severely persecuted. In turn, they were eagerly adopted by opponents of the Kremlin, in particular, the German Nazis, who tried to use pan-Turkism both to destabilize the situation in Turkey itself and to undermine Soviet influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

However, Ankara (it became the capital of the Turkish Republic in 1923), faithful to Ataturk's legacy, has always been wary of this topic. In 1944, Turkish President Ismet Inonu called pan-Turkism an «enemy» ideology that threatens the country with «troubles and catastrophes». After that, some prominent pan-Turkists, in particular, the Bashkir Ahmet-Zaki Validov were thrown behind bars and, although later most of them were freed on appeal, pan-Turkist rhetoric, usually heavily mixed with chauvinism, remained the domain of mainly marginals. Convinced, in particular, that the genocide of Armenians and Greeks never happened, and that the inhabitants of pre-Columbian America, like Fyodor Dostoevsky, were Turks.

New force

After the collapse of the USSR, Turkey became one of the contenders for dominance in Central Asia. In 1992, a new agency was created in Ankara — the Turkish Agency for International Cooperation and Development, designed to coordinate assistance to foreign countries, primarily the states of Central Asia and Transcaucasia, and a separate department for Central Asian countries appeared in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, by the early 2000s, Ankara's claims to political leadership in the region were exhausted. Turkey's attempts to interfere in the processes of state-building of the post-Soviet republics were categorically rejected locally, and in the case of Uzbekistan, it almost came to open confrontation when Ankara decided to shelter political opponents of Islam Karimov.

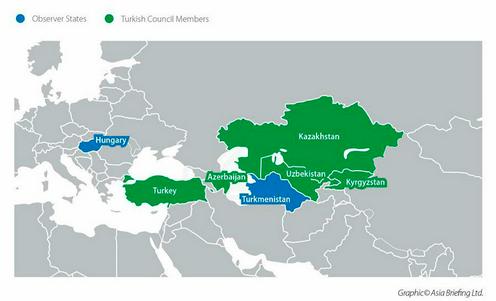

If any pan-Turkism can be traced today, its influence is limited mainly to the cultural sphere and support for interstate relations at the level of the Assembly of Turkic Peoples or the Organization of Turkic States. Although during the presidency of Recep Erdogan, pan-Turkic narratives began to sound more often in Turkish politics, they still do not have a decisive influence on decisions made by Ankara. Plus, the closer to the end of the current head of state's last term, the more challenges arise that the Turkish economy has to face, so geopolitical adventures are clearly irrelevant in light of rapidly growing inflation and income inequality.

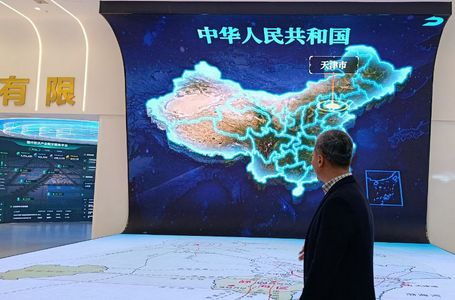

In addition, the same obstacles still stand between Turkey and Central Asia — Russia, Iran and the Caspian, and attempts to somehow overcome the latter through the construction of a trans-Caspian gas pipeline that would connect Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan with Azerbaijan have not been successful so far. On the other hand, both figuratively and literally, a new force has formed next to Central Asia, China, whose role in the region is constantly growing and which does not care at all what textbooks Turkish students and schoolchildren will study from.

-

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

01 November01.11Catching Up with UzbekistanAlisher Aminov on the Problems of Kazakh Football and Plans to Fix Them

01 November01.11Catching Up with UzbekistanAlisher Aminov on the Problems of Kazakh Football and Plans to Fix Them -

03 October03.10Will SKAI Help?Neural Network Joins the Board of Kazakhstan’s Sovereign Wealth Fund Samruk-Kazyna

03 October03.10Will SKAI Help?Neural Network Joins the Board of Kazakhstan’s Sovereign Wealth Fund Samruk-Kazyna -

02 October02.10Football, Presidential StyleKFF Secretary General David Loria on the expansion of the Premier League, the new national team coach, and Tokayev’s role in Kazakh football

02 October02.10Football, Presidential StyleKFF Secretary General David Loria on the expansion of the Premier League, the new national team coach, and Tokayev’s role in Kazakh football