The 12th February this year marked 30 years since the tragic February events in Dushanbe that became the prelude to the Tajik Civil War of 1992-1997. During the dispersal of demonstrations and the suppression of rioting that began in the capital city that day, 25 people died and hundreds more were injured. The events of what has come to be known as “Black February” have been described in detail by a multitude of different witnesses, yet their accounts often differ markedly from one another. For this reason, in order to piece together as reliable a picture as possible of what occurred on these days in 1990, it is vital to gather the testimony of as many different eyewitnesses as possible.

Russian journalist and political commentator Andrey Zakhvatov was a direct participant in the events in Dushanbe 30 years ago. He shared with Fergana his thoughts on what happened during those few hectic days, plus a number of little-known facts about the February events.

How it all unfolded

The massive public disturbances in Dushanbe in February 1990 began after rumours of unknown origin started spreading about apartments being allocated to Armenian refugees. Fired up by these rumours, on 11 February, several hundred youths, some of them brought in from nearby villages, gathered outside the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Tajikistan on Lenin Square to demonstrate, demanding the Armenians’ eviction. In reality, there had been no such allocation of apartments to refugees, and the number of Armenians who arrived in Dushanbe and were being put up there by friends and relatives was no more than a few dozen individuals. They received only a small amount of financial aid from the government and nothing more.

The following day, the demonstrators assembled once again, and after calling for the deportation of refugees, began to demand the resignation of the country’s leadership. Heavy clashes broke out between the demonstrators and police and army soldiers guarding the Central Committee headquarters. It is still not known who it was who ordered shots to be fired from the building – it is not impossible that the troops themselves took the decision to use their weapons after the crowd succeeded in bursting inside.

The demonstrators’ response to the shots fired against them took everybody by surprise: large groups of them, mixed in with criminal elements who joined the rising chaos, began rioting and vandalising the city centre, and then, aided by youths from surrounding villages, continued their rampage in the suburbs.

Over the three days in which the rioting continued in the city, on various accounts between 24 and 26 people were killed, including five Russian citizens, two Uzbeks and two Tatars – the rest being Tajik citizens. More than 550 people of many different nationalities were assaulted and suffered injury. According to official information, over the course of the riots, 17.2 million roubles of damage was caused. The Water Management Ministry adjacent to the Central Committee building was damaged and partially looted. The rioting mob trashed and plundered the Barakat food market, as well as a number of businesses and stores operating under the Ministry of Trade’s Tajik Consumers’ Union, with the Union’s jewellers’ store suffering the greatest losses – 1.36 million roubles.

By the evening of the 12th of February and the morning of the 13th, the pogroms and beatings had spread to the whole city. A climate of fear was hanging over Dushanbe. Only on the evening of 13 February were troops and tanks called in to the capital, and by 14 February the rioting had been brought to a stop.

Pretexts, causes and roots

Assessing the events in Dushanbe thirty years ago, historians contend that the rumours and calls to expel Armenians were merely a pretext for the start of the riots. In the opinion of the Tajik opposition, engaged from 1992 in full-scale armed conflict with the central government, the chief cause of the February events was the population’s dissatisfaction with the communist government of the day. There was also talk of the involvement of foreign intelligence services and even of the Afghan mujahideen.

In a number of works published over the last 10-15 years, there are accounts of the participation of the internal affairs ministry of the USSR, the KGB and the Soviet armed forces in provoking and then carrying out a swift, pre-planned suppression of the demonstration – as an extension of the earlier tragic events in Tbilisi and Baku. Yet there is no evidence to substantiate any of these claims, nor do they have any foundation in common sense. As an eyewitness to the events, I can give an example to back up my contention.

In response to the unfolding chaos and rioting, local self-defence units started to form in literally all of the municipal districts of Dushanbe. This unique process of civic self-organisation, hitherto unknown in any of the union republics, happened quickly – especially after Communist Party First Secretary Qahhor Mahkamov’s televised call to citizens to arm themselves and defend their homes and their city.

In the course of literally one or two hours during the first half of the 13th of February, 10 units (one for every apartment block) of around 250 men, bearing whatever weapons could be mustered at such short notice but still rather well equipped, had been formed in the Giprozemgorodok residential area where my family lived. The units were composed of residents of various nationalities; Tajiks and Uzbeks made up around half. Literally half an hour after the formation of our unit, a crowd of several hundred angry youths entered our residential area, clashed with our defences and were dispersed.

Once calm had been restored, a short meeting of unit commanders was convened and the decision was taken to send me and the deputy director of the Tajikgiprozem institute, Levan Kokorishvili, to the barracks of the 201st Motor Rifle Division, located next to the Giprozemgorodok residential area, in order to coordinate our units’ activities with those of the military in case the situation should further deteriorate.

The entrance to the division’s base was guarded by an armoured personnel carrier and a platoon of armed soldiers under the command of a major. In answer to our enquiries as to what role had been assigned to the division in the current circumstances, the major answered that Moscow had ordered the soldiers to defend the division’s base, its weapons stocks and munitions, and not to get involved in “the civil conflict”. The officer also said that, until the end of the crisis, women and children from our residential area would be permitted to enter the barracks, where they would receive food and drink. Nevertheless, our proposal to cooperate was put into effect: the major had apparently reported back to the division commander, and soldiers in armoured personnel carriers began to regularly patrol our residential area, which made the defence of our territory a great deal easier for us, especially at night.

Not just I, but a number of my journalist colleagues and other experts too are convinced that the fundamental causes of “Black February” in fact lie much deeper than was imaginable 30 years ago. One of the two chief causes that formed such ideal conditions for the eruption of popular dissatisfaction with the authorities is, in my view, the high tempo of population growth in the Central Asian republics as a whole, and Tajikistan in particular. Here’s why.

At the end of the 1980s, the issue of the distribution of plots of land for residential building in rural districts with rising populations started to become acute. Not many people are aware of this, but at the end of 1989, the Communist Party committee of the capital city’s October district received a subsequently-classified letter from residents of villages located in the Varzob valley in the suburbs of Dushanbe, administratively part of the city municipality.

People there were angry at the increase in the amount of local land set aside to construct leisure facilities for employees of companies and organisations in the capital, who would travel there from their city-centre apartments on days off and violate the accepted behavioural norms of a Muslim country, by drinking alcohol and walking around in their swimsuits. The crux of the matter, however, was that the letter’s authors were complaining about a shortage of good-quality land to live on.

As the second deep cause behind the eruption of popular discontent and the activation of opposition forces, I would adduce the growth of national consciousness that resulted from Gorbachev’s perestroika and which was interpreted differently by different political forces. In Tajikistan at the end of the 1980s, the oppositional movement Rastokhiz (Revival) emerged, which openly called for the state language to be Tajik and cooperated with the then unofficial and now banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT).

Discussion of issues such as the preservation of the Tajik language, national identity and culture, as well as questions of access to land, immediately graspable to ordinary people and to a large extent highly justified, quite quickly shifted from the realm of kitchen-table conversation to public speeches from the tribunes of communist party meetings and conferences. Thus, in the autumn of 1989, at an October district party conference held at Dushanbe’s Lahuti Theatre, a leading Tajik intellectual stood before delegates and pronounced the following, previously-unthinkable words: “Comrade deputies, look at the texts of your mandates: the Russian and the Tajik texts are almost identical. We Tajiks are forgetting our language, our national culture...”

Thus, by February 1990, all the preconditions were in place for a major claim to power on the part of opposition forces in Tajikistan. In frantic conditions, a “Committee of 17” was formed to conduct talks with the authorities in Dushanbe, composed of members of Rastokhiz, several highly-placed officials, some leading academic and cultural figures in the country, and representatives of those who had gathered to demonstrate.

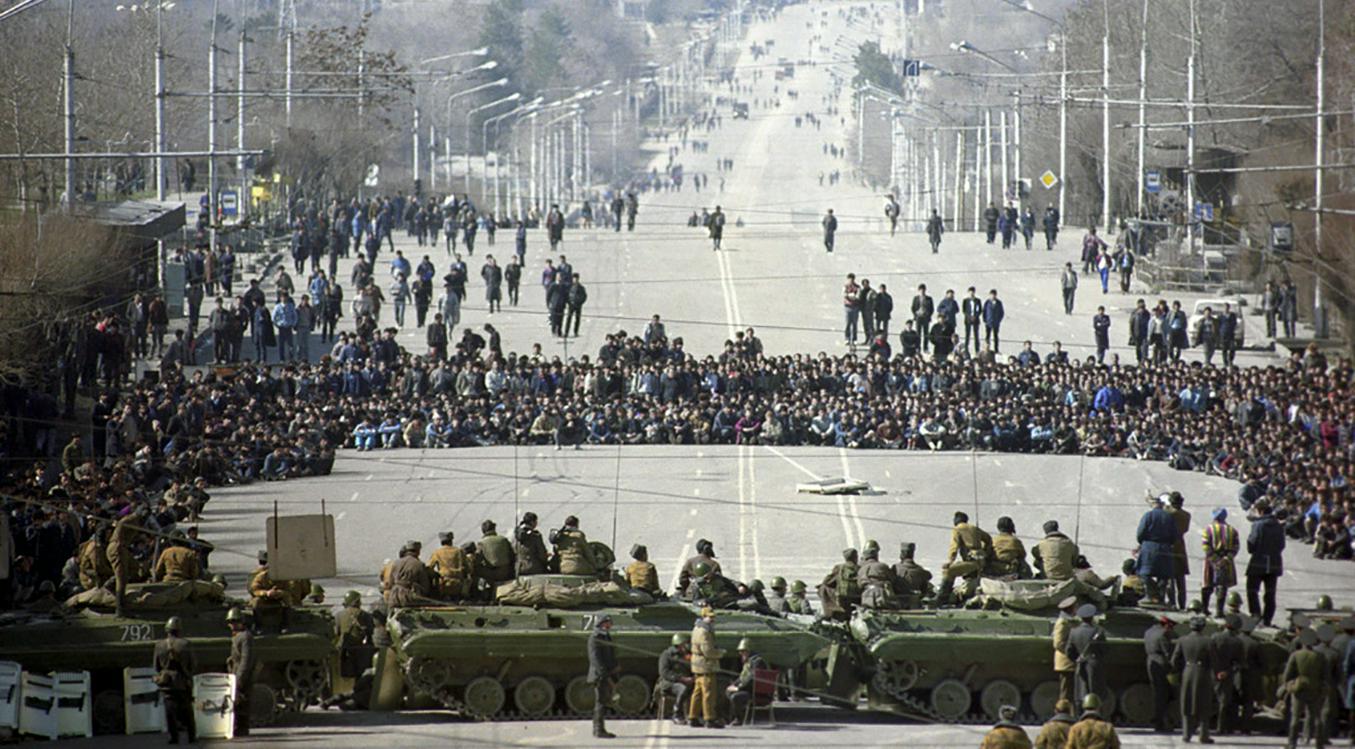

Soldiers in the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Tajikistan. Photo by Vladimir Fedorenko from wikipedia.org

Soldiers in the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Tajikistan. Photo by Vladimir Fedorenko from wikipedia.org

The genocide that wasn’t

The events of those few February days in Dushanbe shook the whole country, but reliably establishing who it was who had an interest in leading people to the Central Committee headquarters, who turned the anti-Armenian chants into anti-government ones and who initiated the shooting and the pogroms has proved impossible, despite dozens of investigators being brought in from the internal affairs ministries, the KGB and the offices of the prosecutor-generals of both Tajikistan and the USSR.

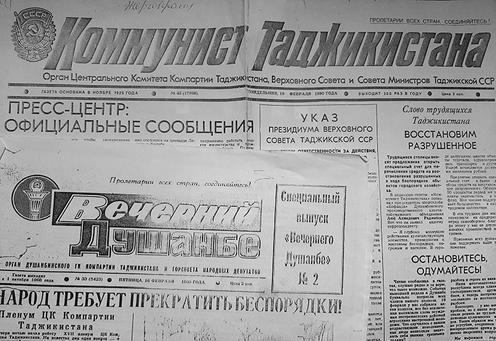

Besides this, state television in Moscow maintained a strict silence on the worrying news coming out of Dushanbe. When this happens, the information vacuum immediately gets filled by rumour, contradictory stories and fabrications. As a result of this, the February events have for many years now been submerged and distorted by innumerable purported “eyewitness accounts” and the analyses of pseudo-experts and politicians.

The most notorious example of disinformation about the Black February events is a section of a book published in 2008 entitled Враг народа (Enemy of the People), by the well-known Russian politician Dmitry Rogozin, who wrote: “Typically, the frenzied nationalists’ first victims were peaceful Russian residents. For example, the internecine slaughter between “vovchiks” and “yurchiks” in Tajikistan (the popular Russian names for the two sides in the Tajik civil war; the former from the religious label “Wahhabis” for the opposition forces, and the latter for the pro-government forces, from the name of former Soviet leader Yuri Andropov – Fergana) was preceded by reprisals against the Russian population in Dushanbe and other cities. In mid-February 1990, the nationalist-Islamists literally tore one and a half thousand Russia men and women to pieces in Dushanbe. Under the thunder of machine guns and the cackling of thugs and rapists, women were forced to undress and run in circles on the square outside the central train station.”

It is hard to say where the Russian politician obtained his “information” about the “genocide” of Russians that occurred neither in 1990 nor during the following years of protracted warfare. As a direct participant in the events, I can testify to this: yes, there were Russians, along with members of other nationalities, who were killed during these days, and several hundred of them were assaulted (together with a similar number of Tajiks), but talk of mass reprisals and the “tearing to pieces” of one and a half thousand Russians is simply not true.

Rather more accurate, in my view, is the assessment of the February events given by the Tajik historian Ibrohim Usmonov: “The youth in Tajikistan in those days understood democracy to mean the power to do whatever they wanted. I do not think that we could have established peace in Tajikistan simply by crushing that demonstration. The events of February 1990 in Tajikistan were not directed against any one nationality. The civil war in Tajikistan could have been avoided if we had succeeded in drawing the correct lessons in time from the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

The order came to disband

Within less than twenty-four hours of the start of the riots, a curfew had been introduced and several hundred troops were flown in from Russia to establish control over key strategic sites around the city. Real control over the city, however, especially at night, was assumed by the commanders of the self-defence militias. It was they who really stood up to the violence of the rioting youths. On the morning of 16 February, around 20 unit commanders who had managed to coordinate their actions met at the headquarters of the city executive committee to discuss the creation of a unit commanders’ council.

This informal paramilitary organ of local self-government, formed by civil society, could have played a significant role in later events. On the very same day, however, the chairman of the Central Control Commission of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Boris Pugo, newly arrived from Moscow, delivered a speech to an extraordinary plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Tajikistan in Dushanbe, and events unfolded according to a scenario dictated from Moscow.

Published in the newspapers, the essentially empty speech of this envoy from Moscow, who later attained the rank of colonel general and the position of internal affairs minister of the Soviet Union but committed suicide immediately after the military putsch of August 1991, contained only grandiloquent pronouncements about the greatness of the Communist Party and not a single word of thanks to the ordinary citizens who had taken to the streets to protect the city from bandits. The previously-terrified local authorities felt that the threat to their power had passed and insisted on the disbandment of the citizens’ self-defence units. The voluntary surrender of firearms began all around the city, but the units continued to defend their territories for a number weeks yet. People were angry at the spinelessness of the authorities, but placated by the fact that not a single criminal charge was brought against any commanders or ordinary members of the paramilitary units, despite them having formally broken the law, inflicting at times serious injuries on the rioters.

In place of a conclusion

During the 1990s, the ethnic composition of the newly independent Tajikistan underwent fundamental changes. Many of those who had been involved in the February events soon left the country, and part of the documentary evidence from those days was either burned or otherwise lost from the archives during the country’s civil war.

According to some reports, the then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev admitted that he did not know who had given the order to fire on the demonstrators and who it was who had led the rioting in the city. In all probability, these questions will remain unanswered. Over the last 30 years, none of those who were involved in the February events has taken responsibility for the decisions that were taken, except for Qahhor Mahkamov. Many who were there at the time feel that his televised speech calling on Dushanbe residents to defend themselves saved not a small number of lives. Most of the high-ranking ministers and generals in both Moscow and Dushanbe who played a part in the February events are no longer alive.

In all the years since the events of February 1990, not once has the current regime in Dushanbe thanked the city’s residents for the resolve they demonstrated during these difficult days, and never does it mention the role of the civil population of the city in standing up to the rioters. It is just like the title of the crime drama by the Italian director Damiano Damiani: “The Case Is Closed, Forget It”. Yet, had it not been for the spontaneous popular militias, the consequences of the events could have been far, far more tragic.

Andrey Zakhvatov

Translated by Nick L.

-

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

25 September25.09I Am Proud to Have Been Part of the Triumph of the Tajikistan National TeamGela Shekiladze sums up three years in Tajik football

25 September25.09I Am Proud to Have Been Part of the Triumph of the Tajikistan National TeamGela Shekiladze sums up three years in Tajik football -

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance -

18 June18.06Unconditional Eternal FriendshipWhat China Offers Central Asian Countries

18 June18.06Unconditional Eternal FriendshipWhat China Offers Central Asian Countries