Spring in Uzbekistan is the peak of tourist season, a time of landscapes of indescribable beauty and exciting journeys through blooming nature. But it ends very quickly—sometimes abruptly. Summer can arrive as early as May, bleaching the sky with forty-degree heat and scorching the vivid spring greenery to yellow.

To enjoy the final days of spring 2025, I tagged along on a trip with professional guide Ivan Belikov, head of the Tashkent Off-Road Travel Club. In a diesel SsangYong Musso SUV from 1998, we covered 2,000 kilometers in two days, visiting numerous landmarks across the mountainous south of the country on a single route. All of them are well worth the attention of travelers and, once seen, linger vividly in the imagination for years. I will describe the most memorable—and at the same time, the most accessible—of them. Every photo in my report was taken no more than three steps from the car. This is a guide for the laziest auto-tourists, those who prefer comfort over physical exertion.

Artifacts of the Cold War

The high-mountain plateau of Maidanak in the Gissar Range is located in a picturesque area of Kamashi District, Kashkadarya Region, at an altitude of 2,750 meters above sea level—45 kilometers southeast of the city of Shakhrisabz. The surrounding landscape is made up of basalt and dolomite cliffs and slabs, covered with alpine meadows and sparse juniper forests of archa, a tree-like species of juniper. The air here is piercingly fresh and clean, filled with the scent of needles. Because of its unique astroclimatic conditions—crystal-clear skies and a high number of sunny days—an astronomical research observatory was built on a nearby peak of the plateau in the 1970s. But within a decade, it was relocated to neighboring heights. In its place was established the Maidanak Separate Command and Measurement Complex (OKIK Maidanak, Military Unit 50065) of the Soviet Union’s Space Forces. It consisted of two large telescopes—one equatorial and one azimuthal—as well as numerous pieces of additional equipment.

The main function of the Sirius quantum-optical system was to track artificial Earth satellites—both domestic and foreign. The equipment was also capable of emitting laser beams to blind satellites of a “potential adversary.”

In December 1992, the Maidanak Separate Command and Measurement Complex was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Russian Aerospace Forces. In March 1993, Russian military personnel completely withdrew from the plateau, handing over the complex to Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Defense with a promise that some data from the telescopes would continue to be shared. In 1994–1995, the possibility of integrating the complex into the American near-Earth object tracking network was also explored. Subsequent political developments in the region rendered both plans obsolete. However, work on laser rangefinding of spacecraft continued at the site until 2016. Shortly after those operations ended, tourists began visiting the plateau. In 2023, the military unit was officially disbanded. Even so, the telescopes' optical systems are still kept in working condition. At night, various objects in the solar system can be observed through them.

Today, visitors can freely drive up to the platform in front of the telescopes. Moreover, the complex is already being converted into a tourist center, with plans to build 24 comfortable cottages, a high-altitude restaurant, and other guest infrastructure—already slated for completion by the next tourist season. We were lucky to catch a glimpse of the Maidanak complex before its reconstruction, to take a journey back in time and witness, against the backdrop of the icy peaks of the Gissar Range, the fantastical rusting structures of a bygone era, evoking the familiar phrase: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…”

Sanctuary of the Gissar Mountains

Settlements named Langar—which translates as “anchor” or “haven”—can be found in abundance throughout landlocked Uzbekistan, often several per region. But this has nothing to do with the sea and everything to do with the spirit. In the Middle Ages, places called Langar were often those where members of various orders of wandering dervishes—Sufi brotherhoods—found refuge or established khanaqas, waystations for rest and prayer. Among them, the Langar located in Kamashi District, which we reached after descending from the Maidanak plateau, is perhaps the most renowned.

According to legend, Langar was founded in the 15th century by Sheikh Muhammad Sadiq, the son and grandson of Sufis. While he was still a murid, or disciple, of a great master of the Ishqiya brotherhood, one of his duties was to bring his teacher warm water for ablution each day. One day, when no firewood could be found for the hearth, he tucked the vessel of water into his robe, wrapped himself tightly in its folds, and dozed off. While he slept, the water came to a boil. Upon learning this, the master declared that Muhammad had clearly attained the highest levels of the spiritual path and must now establish his own community. There was no longer a reason for them to remain together. He was told to mount a camel and travel in any direction until the animal collapsed from exhaustion and could not rise for three days. That happened in a beautiful mountain gorge, where Muhammad Sadiq chose to stay and enlighten his followers.

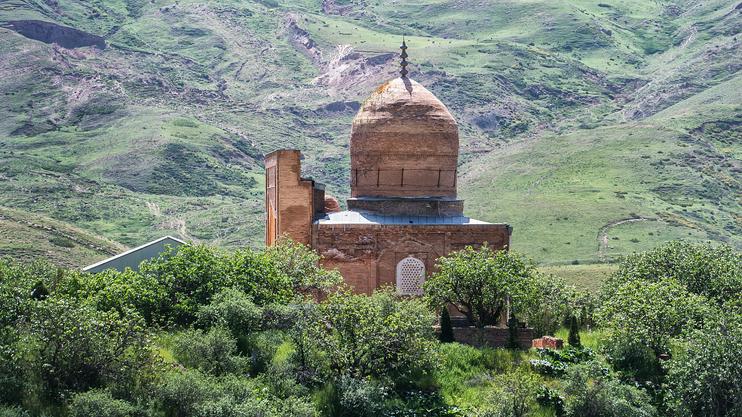

By the 16th century, Langar had grown into a sizable settlement, at the highest point of which a mausoleum was built for Muhammad Sadiq, who became known among the people as Langar-Ota. Over the centuries, the mazar was surrounded by a cemetery where more than 300 prominent Sufi followers were laid to rest.

On the opposite hill stands the medieval Langar-Ota Mosque, also dating back to the 16th century. Both sites have undergone restoration in recent years, but largely retain their original appearance. Notably, most of the individuals buried in the cemetery around Muhammad Sadiq’s mausoleum—judging by the dates on their tombstones—lived well into their 80s and 90s. This may point to unusually robust health, either due to the conditions of the region, a virtuous way of life, or both.

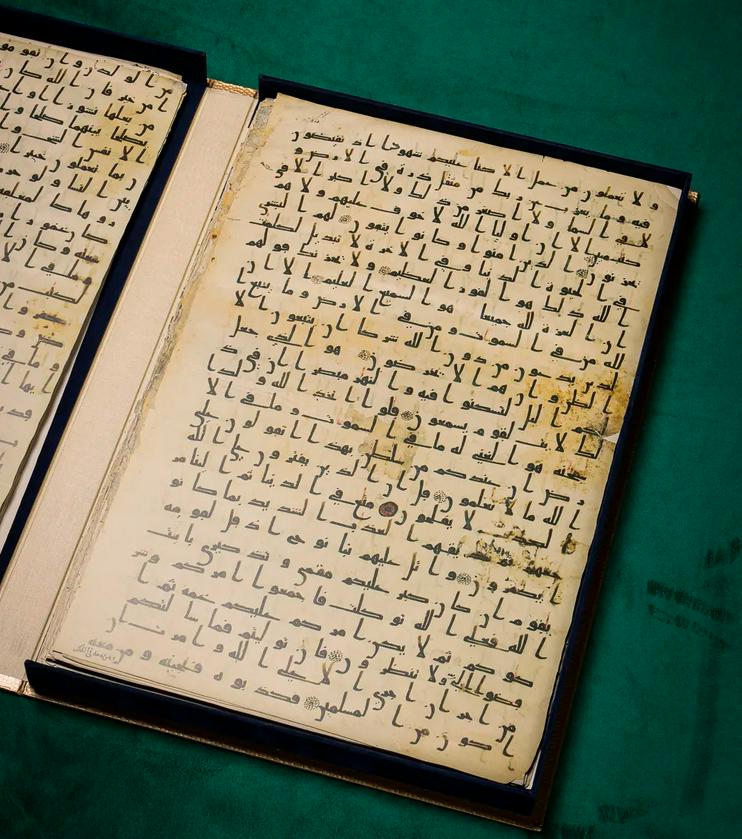

The Langar of Kamashi—or, as it is often called today, Katta Langar (“Great Langar”)—gained considerable renown in the Muslim world because one of Islam’s sacred relics was preserved for a long time within its Sufi community: a handwritten Qur’an believed to date back to the 7th century, from the time of the righteous Caliph Uthman. According to scholars, the Katta Langar Qur’an is one of six original copies of the Uthman Qur’an that were sent to different parts of the caliphate to codify the faith in its orthodox form.

In the late 19th century, 81 of its 206 pages were taken to Russia for a private collection and later ended up in the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. In 1984, 67 pages were appropriated by local officials, and their whereabouts remain unknown. Seventeen more pages remain in Uzbekistan. The World Society for the Study, Preservation and Popularization of the Cultural Heritage of Uzbekistan (WOSCU) continues to search for, study, restore, and raise awareness of this unique artifact of Islamic civilization.

European tourists may be drawn to Langar not only by its legendary history but also by its distinctive present. One can see processions of pilgrims and observe the exotic daily life of rural residents in their traditional homes, whose appearance has changed little over the centuries. Unlike in other regions of Uzbekistan, the ordinary houses here have a striking and colorful character. Built from local mountain stone of an unusually vibrant, cherry-tinted hue, they blend in with the surrounding pristine landscape, which is painted in the same vivid tones.

Baysun Anomalies

Our fast-paced road trip nearly came to an abrupt end near Dehkanabad—a small district center on the steppe border between Kashkadarya and Surkhandarya regions. The SsangYong Musso, which had run for nearly thirty years without serious breakdowns, suddenly began to lurch on a relatively smooth stretch of highway. A quick inspection revealed that the left steering shaft had failed. It happens eventually. This wasn’t a minor issue—no jack, wrench, or curse word could fix it. We needed a tow truck and a full-service auto repair shop to replace the broken part. But where could you find those in the middle of a barren steppe, especially at the end of the day?!

I know nothing about machinery except for cameras and couldn’t have helped the driver even with advice. So I hitchhiked toward Baysun. Ivan also got into a passing car but soon got out in Dehkanabad near the bus station, planning to find the right specialists through the local drivers. “With diplomacy, you can solve any problem in the East. Or almost any. And I have a black belt in diplomacy,” the seasoned guide assured me. I rode on, fatalistically deciding to focus on my own photographic tasks. That’s how I’ve learned to act in any situation I don’t understand.

A hundred kilometers later, Baysun unfolded before me in a broad foothill valley—Uzbekistan’s southern tourist capital. A city of legend. Compass and pole. Surrounded by a constellation of natural beauty and wonders, the town itself is a sight to behold. I’ve visited Baysun many times and will likely return again and again. It never fails to surprise me—and always rewards the eye.

This time, the intrigue began even before I reached the city—at a lookout point by the entrance to Baysun. It turns out that in just the seven years since my last visit, the administrative center of the district, home to around 30,000 people, has changed dramatically. A majestic new mosque now rises over the city, along with a few blocks of multi-story residential buildings. A government-led renovation program, accompanied by a private construction boom, has finally reached this remote area.

Those who prize authenticity and remember Baysun as a bastion of traditional one-story architecture might clutch their heads reading this—and then start throwing ashes on them. But I don’t rush to judgment before taking a closer look. And this time, it turned out that the renovations had radically transformed only one central neighborhood—unique in its own right, to be fair. The city’s other, equally distinctive districts remain untouched and will likely stay that way for decades to come.

For me, one unquestionable benefit of these changes is the arrival of several modern hotels. At the start of the 21st century, you could only spend the night in Baysun if you knew someone. Ten years ago, the first guesthouses with decent service began to appear. At the time, tour operators guarded their addresses like revolutionaries hiding safehouses from the secret police. I do enjoy the cozy charm and rustic flavor of guesthouses—especially somewhere like Gilan. But in a bigger town, even one at the edge of the world, I always prefer to stay in a modern hotel.

Taking a friend’s recommendation, I checked into the Gaza Hotel (emphasis on the last syllable), located in the mahalla—or neighborhood—of the same name on the western edge of town. A cozy single room with a functioning winter-summer climate control system, a hot-water shower, working TV, decent breakfast included, and a restaurant open from 7 a.m. to midnight cost me 250,000 Uzbek soums (about $19). I’d say that’s a great deal.

Before sunset, I managed to visit Baysun’s own natural anomaly—Kyzyl Canyon (“Red Canyon”). This surreal 30-kilometer-long ravine carved into loess formations, with elevation drops of up to 50 meters, lies just three kilometers from the city center—and only about a kilometer from the Gaza Hotel. The friable sedimentary rock, once lifted from the Tethys seabed by tectonic forces, has been sculpted into fantastic labyrinths by spring floods and rains over the centuries.

As a landscape photography specialist, I recommend that anyone hoping to capture Kyzyl Canyon choose late autumn and partly cloudy skies. At the very least, aim to shoot just before or after sunset. In the daytime, especially under clear skies, even the canyon’s surreal formations can appear flat and underwhelming. It’s no Grand Canyon—but even the Grand Canyon is best viewed in the right light. And in summer? Let’s just say the Baysun canyon turns into the throat of hell. Surxondaryo Region in Uzbekistan lies in the dry subtropics—geographically, not metaphorically—with all the climatic consequences that implies.

Around midnight, Ivan arrived at the hotel—driving a fully repaired car. Thanks to some driver connections at the Dekhkanabad bus station, he’d managed to find both a tow truck and a workshop that replaced the faulty steering component in just five hours. I was impressed. I had already started looking at flight options from Termez to Tashkent. But it turns out that today, even in southern Uzbekistan, it’s possible to navigate a serious roadside crisis fairly quickly. Or maybe we just got lucky. Or maybe Belikov really does have a black belt in diplomacy. Who am I to say?

In the morning, with the repaired SUV, we set out for Padan—a scenic site just 12 kilometers from Baysun, though not down into the canyon but up into the mountains. This picturesque valley is known as the venue for the traditional ethnographic festival Baysun Bahori (“Baysun Spring”). Ivan chose a large, relatively flat green meadow on the saddle between two mountain peaks and marked its GPS coordinates as the future rendezvous point for a caravan of off-road vehicles carrying Russian tourists. That, in fact, was the purpose of his trip to Baysun: scouting the location for the upcoming event.

It’s a spectacular spot. On one side, there’s a view of Baysun; on the other, a stunning panorama of the rocky ridges of Tamtut and Chulbair, whose slopes are thickly forested with towering, centuries-old juniper trees. And if any of the tourists have second thoughts about camping overnight, it’s an easy ride back to a hotel in town.

Belikov’s mission was now complete. As for me, I would gladly have stayed in Baysun for several more days—there’s always something to do there. But on this fast-paced road trip, I was just a passenger, and I embraced the role, trying to get the most out of it.

The Padan “Gravity Lift”

While in Padan, Belikov showed me the area’s most famous “Baysun anomaly”—a roughly 40-meter stretch of mountain road where a car, without any propulsion, supposedly moves uphill against both common sense and the laws of physics. This phenomenon has been written about extensively, with videos comparing it to similar places in Israel (Beit Shemesh), Jordan (Devil’s Slope), India (Ladakh), Russia’s Middle Urals (Nevyansk District), and South Korea (Jeju Island).

I’m not a committed skeptic, but as a journalist, I couldn’t help noticing that no serious scientists have ever bothered to comment on this “miracle.” Perhaps they view it as such an obvious absurdity that it doesn’t warrant any explanation. On social media, I found users noting that not a single guide or local enthusiast had ever thought to record the elevation data using GPS at both the start and end of the “anomaly.”

Skeptics claim that what we’re dealing with is actually an optical illusion that distorts perception. In reality, the road slopes downward, but to the observer it appears to rise. As a photographer, I also find it hard to believe that gravitational or electromagnetic forces strong enough to pull a car uphill would leave something as fragile as the human body entirely unaffected. Optics, however—that’s another story! From experience, I know just how deceptive the eye can be, often with no consequence whatsoever for physical objects or living beings.

We, too, shot a few videos of the “anomaly,” gleefully releasing the SsangYong Musso into it with the driver and passengers out of the car and the drivetrain disengaged. Standing nearby, it really does feel like the vehicle, once the handbrake is released, is moving uphill on its own. You can even trot after it without breaking a sweat. But from a significant distance, I filmed a segment where the “uphill” stretch suddenly appears less convincing and looks more like a descent. Still, I’ll refrain from drawing any firm conclusions, leaving that to the readers—many of whom likely understand the mechanics of the universe far better than I do.

We returned through the Darband Gorge—another of Baysun’s tourist draws, located just 20 kilometers west of the city. The gorge looks so dramatic that many believe it to be the legendary “Iron Gates” stormed by Alexander the Great, behind which—according to classical and early medieval legends—he sealed off the monstrous barbarian tribes of Gog and Magog until the end of days. In truth, the “Iron Gates” refers to a comparatively narrow section of the modern M39 highway between Termez and Tashkent, which passes near Baysun through the kishlak (village) of Shurob.

The Darband Gorge stretches for eight kilometers, a strikingly narrow fissure carved over millennia into the rock by the flow of the Machaidarya River. In some places, the pass is barely thirty meters wide, and the grim cliffs even arch overhead to form a natural vault. Yet each day, dozens of pilgrims stream into this crevice in the earth to visit the sacred spring and the mausoleum of Khuzhamoy-Ota.

According to legend—one of many such tales heard throughout Central Asia—in a year of terrible drought, famine, and disease, a righteous man prayed to the Almighty. God showed him the place to strike with his staff, and from the rock burst forth a spring of crystal-clear water, teeming with edible fish. Indeed, a powerful stream of water still gushes from the foot of a sheer cliff here, seemingly out of nowhere.

Today, the spring is enclosed by a structure known as Khuzhamoy-Khona (or Khuzha Mokhi Khona, in another transliteration). The fish are gone, but pilgrims remain, scooping up healing water in any container they can find. Families and groups of men settle into deep rock niches to rest. Caves and grottos abound. Some visitors perform khudoi—the ritual sacrifice of sheep—for blessings or deliverance from misfortune. Most simply drink the water and relax in the cool shade. The sun reaches the gorge only at midday, creating a distinct microclimate.

Just beyond the pilgrimage site, on the opposite bank by the bridge over the Machaidarya, lies the entrance to a breathtaking series of narrows with towering walls and an extremely tight labyrinthine passage. Cutting through the rocky massif, these narrows open out into the steppe valley of the Kichik-Urardarya River—still almost entirely uninhabited, but eventually leading to the M39 highway.

An hour later, the sun sank into the blooming steppe near Dekhkanabad. We hit the road again and sped towards Tashkent. Stopping only for dinner in Samarkand, we returned home that same night. The road trip took just under two days, but it left a wealth of unforgettable impressions, much like a grand adventure.