Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev has agreed to a proposal by the country’s coronavirus taskforce to extend the present lockdown, Uzbekistan’s second since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The announcement was made during the course of a government meeting yesterday, 23 July. Mirziyoyev did not set any specific date for the lockdown’s end.

The president also stated that 46,500 extra hospital beds have been set up around the country in recent days and that work is currently going on to set up 31,000 more. Earlier this month it was stated that the total capacity for coronavirus patients was just 7,500 beds. 397 extra ambulances have also been purchased, with plans to acquire a further 409 by the end of the month.

In order to increase capacity, Uzbekistan has recently changed its procedures to allow asymptomatic and mild patients to recover at home, permitted private clinics to treat coronavirus patients, placed all Tashkent polyclinics on 24-hour operation to assist patients with mild symptoms and increased emergency services capacity, and converted exhibition centre Uzexpomarkaz into a backup facility for the reception and diagnosis of suspected coronavirus cases.

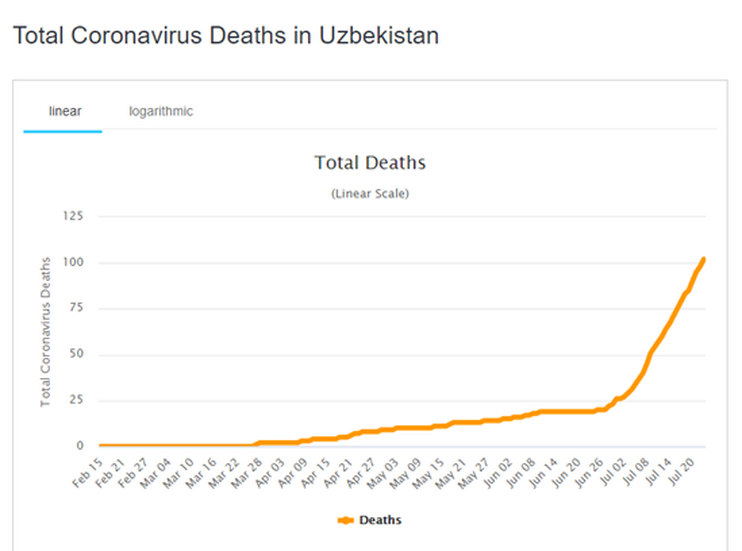

Uzbekistan’s second nationwide lockdown was initially scheduled to end on 1 August, but rumours have been circulating in recent days about a possible extension given that the current rise in cases shows no signs of slowing down. After several months of relatively slow progression, infection figures have risen particularly sharply in the last 2-3 weeks. Since 8 July, daily new case numbers have been between 400 and 600 (with a record 707 new cases on 20 July) and the number of active cases has risen to almost 9,000, from around 2,500 at the end of June. The number of seriously ill patients and cases of pneumonia has also grown quickly during July, with the changing situation most clearly visible on a chart of the country’s death figures to date.

So far Uzbekistan has avoided the kind of surge seen in recent weeks in neighbouring Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan – with an average of just four or five deaths a day being recorded in Uzbekistan, compared to up to a hundred in the far smaller Kyrgyzstan (which has, however, recently begun to include pneumonia cases in its statistics and not just positive PCR tests). But, as a recent article on our Russian site makes clear, there is currently an atmosphere of panic around the country that things might soon be heading the same way. The second lockdown on 10 July was justified on the grounds that the country could soon run out of hospital beds. In recent days it has also become clear that medical staff, too, are in short supply. The hardest-hit Tashkent city and wider Tashkent region, where 60% of cases are currently located, has begun a desperate campaign to quickly attract more medical workers. Nurses have apparently been offered $1,470 a month for a 14-day shift, while the average monthly wage in Tashkent is around $360.

At the same time, however, as elsewhere in Central Asia, medical workers are complaining that the authorities are already failing to stick to existing payments obligations. One emergency medical department complained that even normal salaries are being paid late and that they are still waiting to receive four months of COVID-19 bonuses. Many infected medics are also yet to receive the promised $9,800 compensation. One doctor who was infected with the coronavirus at work calculated that the government owed him more than $17,000 in compensation and benefits accrued since the start of the pandemic.

In other respects too, the picture in Uzbekistan is familiar from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan at the start of their respective surges. The rise in demand for PCR tests has begun to far outstrip laboratory capacity, and people are having to wait for a week or more to get their results – and potentially taking far less care not to spread the virus than they otherwise would in the meantime. Changes have now been made so that test results are sent to patients directly, rather than via the country’s epidemiological agency, in the hope of speeding up the process. The panicked atmosphere also means that demand for anti-influenza and anti-viral medication has also shot up to unmanageable levels (demand for anti-flu drug Arbidol, for instance, has increased by more than 200 times since last month), despite the fact that they have no proven effect against COVID-19. In Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, this has led to reports of profiteering and significant state media coverage of efforts to crack down on any such activity and to increase the supply of medication.

Also as elsewhere in Central Asia, major efforts have been made to make up for shortfalls in government help through an extensive mobilisation of voluntary help. Well-known blogger Umid Gafurov, who runs the media project TROLL.UZ, has created a Telegram bot called Yaqinlar to link up volunteers with those in their local area who require help. Doctors and medical students have grouped together to provide basic treatment in people’s homes and consultations online.

In the final and most tragic parallel with events already seen elsewhere in Central Asia, however, it appears that in some instances this help is arriving too late, and that these victims are not finding their way into official COVID-19 statistics. The father of Uzbek director Sarvar Karimov passed away from presumed coronavirus last week, with the whole family subsequently falling sick. According to Karimov’s widely-publicised tweet, the family had tried to call the emergency services for several days. In Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan at the start of their virus surges – before the emergency services were expanded and temporary day hospitals introduced – many people appear to have died unnecessarily due to low ambulance service capacity and emergency services’ attempts to resist hospitalising people in order to preserve fragile hospital capacity. In Karimov’s case, at least according to his tweet, the reason was a little different. The director said that the operator had told him that if his father has a temperature then they cannot send an ambulance. “And I understand them,” Karimov wrote. “They have neither medication nor PPE. Don’t believe the official statistics, take care of yourselves and your loved ones.”